Mikroskobik Küresel Coğrafya: Pandemi ve Coğrafi Ölçeğin Yeniden Üretimi

“Pandeminin beşeri ve ekonomik coğrafyasını kapitalist doğa üretimi ve coğrafi ölçek bağlamında inceleyen Mehmet Barış Kuymulu “Mikroskobik Küresel Coğrafya: Pandemi ve Coğrafi Ölçeğin Yeniden Üretimi” başlıklı yazısında COVID-19’u kapitalist doğa üretiminin küresel ölçekte meydana getirdiği toplumsal bir ürün olarak ele alıyor. Wuhan’dan virüsün yayılımını sermaye birikim ve dolaşım süreçleriyle oluşan kentsel, ulusal ve küresel gibi temel coğrafi ölçekler üzerinden açıklayan Kuymulu, yayılımın tarihsel olarak geliştiğini ve de sermaye, meta ve emek akışının oluşturduğu kanallar vasıtasıyla gerçekleştiğini vurguluyor. Bedenden eve, kentselden ulusal ve küresele kadar tüm coğrafi ölçeklerin pandeminin mekânsal süreçleri tarafından yeniden biçimlendirildiğini iddia ediyor. Kuymulu’ya göre, COVID-19’un gözümüzün önüne serdiği şey, coğrafi ölçeklerin küreselden bedene bir önem hiyerarşisi dâhilinde değil, göreli mekânsal ilişkisellikler dâhilinde anlaşılabileceği ve bu haliyle mikroskobik bir virüsün diğer ölçekleri dönüştürebileceğidir. Bütün toplumsal parametreleri kârlılık prensibine tabi kılan ve insan-doğa ilişkisini sermaye birikim mantığına hapseden kapitalizmin tarihsel eşitsizlikleri perçinlemekle yetinmeyip yenilerini doğurduğuna dikkat çeken Kuymulu, artan eşitsizliklerin mekânsal süreçler gözetilerek tartışılabilmesi için eleştirel coğrafya temelli kuramsal bir yaklaşım sunuyor.”

Confronting ‘Aggressive Urbanism’: Frictional Heterogeneity in the ‘Gezi Protests’ of Turkey

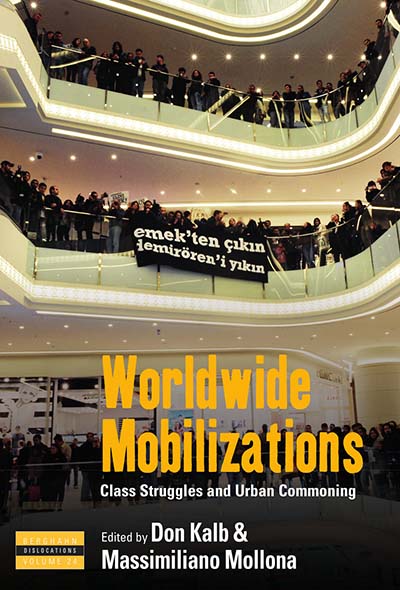

WORLDWIDE MOBILIZATIONS

Class Struggles and Urban Commoning

Edited by Don Kalb and Massimiliano Mollona

256 pages, (June 2018)

ISBN 978-1-78533-906-6

eISBN 978-1-78533-907-3 eBook

https://www.berghahnbooks.com/title/KalbWorldwide

Click to access KalbWorldwide_intro.pdf

“Baris Kuymulu studies the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul and in Turkey at large. Kuymulu engages directly with the ‘middle class’ narrative taken up by the media and pundits and shows that not only a majority of participants were in fact of working-class background but also that what is usually assumed to be the middle classes are in fact much poorer, much more precarious, more downwardly regulated by the neoliberalizing state and, in particular, more indebted than is generally understood by the liberal ‘commentariat’. The protesters also sought and practised forms of urban ‘commoning’ that cannot be captured by the stories of economic growth, private lives and rising consumer expectations associated with the middle-class narrative. Most importantly, perhaps, he traces the emergence of the massive all-Turkey protest wave of 2013 to the ‘aggressive urbanism’ that has been the key engine for economic growth of the AKP regime. He then goes on to show how what he calls a ‘frictional heterogeneity’ developed among protesters of very different persuasions, such as anti-capitalist Islamists and LGBT activists. This practice of frictional heterogeneity helped different actors to identify and negotiate their differences and commonalities in the face of violent police actions. Kuymulu’s chapter is an excellent example of class analysis in the critical junctions mode we are advocating.” (Kalb & Mollona, Introduction, p. 18-19)

CLAIMING THE RIGHT TO THE CITY: TOWARDS THE PRODUCTION OF SPACE FROM BELOW

Unpublished dissertation.

Open access at CUNY Academic Works

https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/439/

For Neil, with Neil.

Abstract

This dissertation examines the theoretical and political contradictions surrounding the notion of the right to the city. The right to the city concept has lately attracted a great deal of attention, both from academics who have long engaged with urban theory and politics, and from grassroots activists around the globe who have been fighting on the ground for an alternative just urbanism. In addition to urbanists and grassroots urban justice activists, the right to the city concept has also drawn considerable attention from the United Nations (UN) agencies such as UN-HABITAT and UNESCO, which have organized meetings and outlined policies to absorb the notion into their own political agendas. This wide-ranging interest has created a conceptual vortex that has pulled discordant political projects behind the banner of the right to the city. By reframing the notion of the right to the city to foreground its roots in Marxian labor theory of value, this dissertation offers a theoretical framework to analyze diverse and often contradictory struggles for realizing the right to the city. Based on two years of ethnographic fieldwork in New York, Boston and Istanbul, the dissertation is organized around the three pillars of the labor theory of value, namely, use value, exchange value and value. It begins with an examination of the political struggles that are mobilized for accessing use values in the city. This is followed by an examination of the UN agencies’ claim over the right to the city that is primarily for realizing exchange values in the city. Although this dissertation acknowledges the usefulness of the analyses of urban political struggles based on the contradiction between use value and exchange value, it concludes with the shortcomings of such analyses and argues for a politics of value, which aims to cast labor in the epicenter of struggles for the right to the city.

Growth and Revolt: Resisting Urban Redevelopment in Turkey

Abstract

As the resistance of 25 activists to protect an urban commons met with heavy police violence in Istanbul in May 2013, the cities of Turkey saw a rapid mobilization of millions that turned this small protest into a full-fledged uprising. Following the path of this political mobilization flowing from Gezi Park to larger geographical scales of the neighborhood, the urban, and the national, the first part of the article analyzes the expanding political geography of the uprising. The second part takes a step back from the heat of the uprising and examines the growth-based political economy of Turkey in the last decade, which gave way to a very diverse, albeit mostly localized resistance that eventually exploded in the uprising cities of Turkey. This article, then, weaves together the right to the city claim that unfolded in urban Turkey and the political economy that enabled such a political mobilization.

Keywords

Gezi Protests, Politics of Scale, Political Economy of Urban Redevelopment, Neoliberal indebtization, Right to the City, Turkey

SOCIOLOGIA URBANA E RURALE Special Issue, “The creative destruction of the Mediterranean city.” Vol. 104. pp. 44-66.

http://www.francoangeli.it/Riviste/Scheda_Rivista.aspx?idArticolo=51708

From ‘Urban Renewal’ to Urban Uprising and Back Again: The Gezi Protests amid ‘Economic Growth’

First published on 3 October 2013 in CritCom (Reviews & Critical Commentary of Council for European Studies at Columbia University)

It has been more than three months since a modest defense of a public park in central Istanbul – initially staged by roughly 40 activists against the government’s plan to turn the park into a shopping mall – quickly became a countrywide urban uprising in the span of three days. The pace and spontaneity of this unprecedented collective mobilization of hundreds of thousands of people without the overt leadership of established and organized actors of Turkey’s democratization, such as leftist trade unions and the Kurdish movement, took many by surprise, especially the governing Justice and Development Party (hereafter AKP, its Turkish acronym).

This initial shock and awe was quickly translated into a search for the uprising’s origins and causes. A ‘specter of comparisons’ haunted the initial analysis. Some argued that the so-called Arab Spring finally knocked on Turkey’s door. Others brought to our attention the similarities between the encampments in New York City’s Zuccotti Park and Gezi Park in Istanbul and the ensuing police violence unleashed in both cities. Still others developed several arguments placing Turkey in the politically boiling southern fringe of Europe, along Greece, Portugal, and Spain.

However, people in the streets of Turkey were not trying to topple an unelected tyrant, calling for the first free elections in recent memory, as Egyptians and Tunisians did. Nor was the reaction clearly directed at a financial elite, holding the rest of the society hostage, as in the United States. Moreover, similarities between the streets of other Mediterranean countries and Turkey’s eventually hit the wall with the comparison between the contracting economies of Greece, Spain, and Portugal, and the relatively constant upward trend in the development of Turkey’s economy throughout the past decade. If all of this was not enough to satisfy the appetite for comparison, protests broke out in Brazil and Bulgaria roughly at the same time that Turkey’s urban protests were grabbing international media attention.

There is nothing wrong, in and of itself, with attempting to understand post-2011 urban mobilizations around the world in relation to one another, as each represents a growing dissatisfaction with a globalized capitalism that is increasingly neo-liberal and authoritarian in character. On the contrary, such connections between distant and apparently unconnected urban mobilizations should be made. However, this commonality in dissatisfaction with authoritarian neo-liberalism seemed to get ‘lost in comparison’, as the theme of the ‘middle class’ became salient when explaining protests that revolved around vague notions such as ‘middle-class movement’ and ‘global middle-class revolution’.[1]

If no one really knew why the people of Turkey abruptly put an end to their apparent long-lasting silence and docility en masse – May Day demonstrations and other exceptions notwithstanding – and if no one could identify the usual suspects (such as trade unions or political parties) behind such a grand mobilization, then, the argument usually goes, it should be a middle-class movement. Let me be clear: By calling into question how quickly the Gezi protests were identified as a middle-class mobilization by many observers, I do not mean to argue that people deemed as middle class were absent from the protests. However, there is a good reason why such broad-based mobilizations around the world are labeled as middle- class movements. This label is ideologically handy for the ruling elite, for media pundits and other fast thinkers, since, what middle classes often demand is more of something that already exists. This can be more democracy, more freedom, or more purchasing power, but such movements are thought to exclude a demand for the wholesale transformation of the social and economic structure that enables such demands. That is to say, the ideological effect of representing the agency of such mobilizations as ‘middle class’ is to imply that hegemonic neo-liberal capitalism is working just fine except for some issues here and there, and that these problems can be solved with a few minor touches.

The middle-class card is especially handy in an explosive situation like the Gezi protests because it also appears to quickly explain why such a grand mobilization took place in a country like Turkey, which has been a star student of the International Monetary Fund, with relatively healthy growth rates in the past decade, unlike the contracting economies of Greece, Italy, and Spain. It is often argued that, while the recent urban mobilizations in the latter countries stem chiefly from austerity measures that inhibited economic growth, the protests in Turkey happened precisely because there was growth, which ostensibly uplifted people’s living standards. Therefore, in order to question the ideological function of postulating a freedom-searching middle class as the agent of social mobilization in Turkey, we should note a few things about Turkey’s so-called economic success.

Caglar Keyder, prominent urbanist and social theorist, argues in his piece, “Law of the Father,” that the protesters in Istanbul were the “beneficiaries of economic growth and greater openness to the world” accomplished by the AKP government.[2] Furthermore, Keyder says, economic growth was coupled with the AKP’s policies that allocated “more money for education,” which led to some 200 universities in total, and the addition of more than 2.5 million new graduates since 2008. Therefore, according to Keyder, greater investment in education, powered by economic growth under AKP’s decade-long rule, gave way to a new middle class that is more open to the world and demands the standards of its global counterparts.

A lot has been made of the growth-based economic success of the AKP government, but it is unfortunate that Keyder’s account, among others, remains uncritical of this success story. It is true that there was an annual growth rate of around 5 percent (fluctuations notwithstanding) throughout the early and mid-2000s, which is deemed healthy by liberal economists. To equate such growth rates with the increase in purchasing power of the population and with the rise in its general standard of living and welfare, however, is to assume that the extra wealth occasioned by economic growth is distributed in such a way as to make up for the existing class inequalities. Even if we brush aside the crucial issues of social justice and look at the growth rates in isolation, which is what many economists do, we would still see worrying signs in Turkey’s numbers. During the global economic crisis, Turkey’s growth rate has fluctuated wildly, from 0.8 in 2008 to -4.8 in 2009, from 9.2 in 2010 to 8.8 in 2011, and to 2.2 in 2012.[3] The estimates for the 2013 growth rate are not sunny, either. According to the optimistic expectations of the AKP government, Turkey’s growth rate will reach 3 percent this year.

Serious fluctuations in Turkey’s growth rates that are synchronized with the systemic global capitalist crisis make sense, considering the long process of neo-liberalization that Turkey has experienced since the early 1980s. However, the malleability of the Turkish economy is still exacerbated by the economic choices that the AKP government has made in the past decade. AKP’s so-called economic success has primarily rested on a high amount of foreign capital flow into Turkey’s economy. According to economist Mustafa Sonmez, the 10 years of AKP rule witnessed an unprecedented $421 billion in foreign capital flow, $340 billion being in the form of unpaid external debt.[4] Most of this foreign capital flowed into Turkey for purchasing state economic enterprises and banks that were put up for sale. Some also went into the Istanbul stock market and government bonds, or came in as loans for the private sector, which is where most external debt is found.[5]

It is not surprising, then, that such unprecedented foreign capital inflow was accompanied by an equally unprecedented pace in the privatization of public assets. Although early attempts of privatization go back to the mid-1980s, it was not until the late 1990s that privatization began to be systematical. Turkey privatized its decades-long accumulated social wealth for $40 billion over 24 years. More than $30 billion of this privatization – i.e., 78 percent of it – took place over the past decade.[6] In just the first half of 2013, the AKP government privatized $8 billion worth of public property, which is a testament to the ongoing accelerated privatization under its rule.[7]

In the context of such rapid and vast privatization of public assets, including urban public lands, the construction sector gained a new prominence during the AKP’s rule. Powered by state-driven urban renewal schemes that have been chiefly about privatization of urban public lands and their development, the construction sector has become one of the driving motors of Turkey’s economy during the AKP period. Yet, as we witnessed in countries such as Spain, this process does not occur without leading to a housing bubble. And bubbles burst, as we are harshly reminded by the systemic crisis that began in housing markets in the United States in 2007. It is also worth noting that, after years of growth, Turkey’s construction sector and its development came to a halt, growing only by 1 percent in 2012.

Privatization and debt-infused development – especially of urban land – together with the constant inflow of foreign capital have been the pillars of the AKP’s political and economic power in the past 10 years. Throughout this period, the AKP transformed Turkey’s urban spaces into a vast construction site, especially through massive and widespread urban renewal projects. It is no accident then that the largest spontaneous social protest in Turkey’s history was mobilized to protect a small public park in the heart of Istanbul from the AKP’s largest urban renewal project, which proposed to transform one of the most iconic urban centers in Turkey – Istanbul’s Taksim Square. Just like the accumulation of capital in one place brings about the accumulation of the working class and hence of resistance, as Marx reminds us, the primary engine of capital accumulation (i.e., the development of urban land and gentrification) led to a massive resistance in Taksim Square at a scale that neither the AKP nor any preceding government had ever seen.

Many people, including myself, argued early on during the Gezi Protests that if Prime Minister Erdogan had not escalated tensions by denouncing the hundreds of thousands of people who were protesting across urban Turkey as merely a few looters, and if he had stopped the urban renewal project, the massive protests would not have turned into a full-fledged urban uprising.[8] However, Prime Minister Erdogan and his government did not pursue that path, and in a way, they could not have done so. Stepping back from the largest urban renewal project designed to transform what is probably the most symbolic and important urban space in Turkey in the face of resistance would have quickly sent a message to many others who are organized against such schemes in their neighborhoods and cities across Turkey that urban renewal can be stopped. It is precisely in order to inhibit this message, I think, that we witnessed such a brutal police crackdown on protesters. However, the resistance sparked by the Gezi Protests did succeed in halting the transformation of Taksim, and the message did get out. It is therefore likely that we will see heightened and more frequent outbursts of resistance across urban Turkey in the coming months, not only because people saw what happened when they protested, but also because the AKP will likely rely more and more on urban development projects in order to increase Turkey’s stagnated growth rate and to put off the looming economic crisis.

[1] See <http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887323873904578571472700348086.html?mod=mktw>, accessed August 6, 2013.

[2] See <www.lrb.co.uk/blog/2013/06/19/caglar-keyder/law-of-the-father/>, accessed August 20, 2013.

[4] See <http://mustafasonmez.net/?p=3412>, accessed August 21, 2013.

[5] See <http://mustafasonmez.net/?p=3539>, accessed August 21, 2013.

[6] See <http://bit.ly/1fMeOg4>, accessed August 5, 2013.

[7] See <http://mustafasonmez.net/?p=3410>.

Reclaiming the right to the city: Reflections on the urban uprisings in Turkey

City: analysis of urban trends, culture, theory, policy, action Volume 17, Issue 3, 2013

Open access at:

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13604813.2013.815450#.Uc6UtOuKTLI

Abstract

The Vortex of Rights: ‘Right to the City’ at a Crossroads

International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. Vol. 37.3, May, 2013. pp. 923-940.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my dear friend, comrade, and mentor Neil Smith

Abstract

The right to the city concept has recently attracted a great deal of attention from radical theorists and grassroots activists of urban justice, who have embraced the notion as a means to analyze and challenge neoliberal urbanism. It has, moreover, drawn considerable attention from United Nations (UN) agencies, which have organized meetings and outlined policies to absorb the notion into their own political agendas. This wide-ranging interest has created a conceptual vortex, pulling together discordant political projects behind the banner of the right to the city. This article analyzes such projects by reframing the right to the city concept to foreground its roots in Marxian labor theory of value. It argues that Lefebvre’s formulation of the right to the city — based on the contradiction between use value and exchange value in capitalist urbanism — is invaluable for analyzing and delineating contradictory urban politics that are pulled into the vortex of the right to the city. Following Lefebvre’s lead in such an analysis, however, reveals certain limitations of Lefebvre’s own account. The article therefore concludes with a theoretical proposition that aims to open up space for further critical debate on the right to the city.

Click to view it at International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

From US with Love: Community Participation, Stakeholder Partnership, and the Exacerbation of Inequality in Rural Jamaica

New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Inquiry. Vol. 4, No. 2, May, 2011. pp. 45-58.

Abstract

This paper examines and argues against the neoliberal assumption that local community participation in market-based nature conservation projects is democratic and leads to community empowerment through economic development. It does so by analyzing the formation of Local Forest Management Committees (LFMCs), instigated by the Nature Conservancy (TNC) and its partnering local environmental NGOs for conserving the tropical forests of Cockpit Country, Jamaica. The paper dissects, specifically, the notion of “stakeholder partnership,” frequently invoked in neoliberal conservation projects in the global south. Such flattening neoliberal terminologies imply a democratic platform, where different groups can express their political agendas and negotiate their differences with equal power. The language of “stakeholder partnership” flattens, this paper argues, hierarchical set of power relations both inherited and exacerbated by free market based conservation projects.